Partner John Milner has written an article for the latest edition of the RICS Built Environment Journal on the end of gas heating in our homes. The article discusses the context, regulations, software, the role of heat pumps, whether hydrogen can play a role and looks at retrofit strategies and standards.

In 1807, the first public gas supply lit 13 street lamps in Pall Mall, London. By 1850 most medium-sized towns and cities in the UK had supplies of coal gas and town gas – gaseous fuels manufactured for sale to consumers and municipalities – and a number of gas appliances were demonstrated at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The popularity of gas fires, gas-fuelled appliances such as space heaters, and boilers increased after the Clean Air Act 1956. Liquefied natural gas was first imported into the UK in 1959, with North Sea gas first discovered in 1965. However, appliances manufactured to burn town or coal gas would not burn natural gas, and the replacement or adaptation of some 20m of these took about ten years from 1967. It was then that gas as we know it today had finally arrived.

Gas usage and living standards increased. Between 1970 and the present, central heating increased from supplying 30% of homes to 95%, with the majority of systems being gas-fired. Modern condensing boilers have been around for more than two decades, and are more than 90% efficient.

However, we now face a climate and ecological emergency, and a major contributor to this is greenhouse gas emissions. To address this, the UK government committed in April this year to reduce carbon emissions by 78% by 2035, having set a target in June 2019 for net zero by 2050 – meaning we must rapidly reduce our emissions.

Residential gas networks are responsible for around 25% of the UK’s carbon emissions. Therefore, the use of gas – primarily to heat the home and provide hot water – needs to fall rapidly. This is likely to be achieved through lowering demand by creating more efficient buildings, and using alternative forms of heating.

Legislative and policy context

The UK Climate Change Act 2008 set legally binding targets for reducing carbon dioxide emissions in the UK by at least 80% by 2050.

In his spring statement of 2019, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond made the bold statement that gas heating for new houses would be banned by 2025.

Last autumn, in the run-up to the COP26 climate change summit being held in Glasgow this November, Prime Minister Boris Johnson outlined his ten-point plan for a green industrial revolution.

Unfortunately, the government has a rather chequered history when it comes to improving the performance of new and existing homes, relying on the market to do the heavy lifting and changing the policy environment with little sign of a strategic plan.

The axing of the zero-carbon standard for new homes in 2015, the failed Green Deal for existing homes, and most recently the dramatic reduction in scale of the Green Homes Grant all illustrate this problem.

Regulatory review

However, the publication of Conservation of fuel power: Approved Document L1A in 2013 does offer some regulatory support, because it sets minimum energy efficiency standards for the fabric of new dwellings and thus establishes a limit on carbon dioxide emissions.

Part L of the Building Regulations has been under review for some years, with an extensive consultation exercise that began in 2019 under the Future Homes Standard. The aim of this review is to provide a route map for the changes needed by 2025 to ensure that new homes are zero-carbon ready and have no gas connections.

In January this year, the government published the summary of responses from the first consultation, which covers changes to Part L as well as Part F on ventilation, for new dwellings.

The second Future Buildings Standard consultation, on existing homes and non-domestic buildings, ended in April. The aim is to publish the new Part L and F documents and overheating guidance by December, to come into effect in June next year.

SAP updates

After June 2022, all new homes will need to emit 31% less carbon than the current standards. This is a stepping stone towards the zero-carbon homes target for 2025.

The current calculation methodology, the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) 2012 for energy rating of dwellings, is due to be published in revised form as SAP 10.3 alongside the new Part L in December, to reflect more up-to-date carbon factors for fuels. These factors enable the calculation of emissions for the fuel used to meet the primary energy demand of the fixed services in a building, whether gas, electricity or both.

The SAP calculation methodology takes the proposed building and creates a digital twin known as the notional building. This seeks to identify the optimal U-values rather than using those from Part L, as well as the best building services specification to comply with the regulations.

In parallel, planning applicants across the country were from January 2019 encouraged to use the updated SAP 10 carbon factors to assess the expected performance of new development.

As a result, the carbon factor of electricity in properties built since then has been reduced by around 45%, which results in fuel factors of 0.21kg of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour for gas, and 0.233kg for electricity. Having encouraged lower-carbon energy consumption, use of these targets has brought the two sources much closer to parity in terms of the emissions generated by their consumption.

New criteria for compliance have also been added. On top of looking at fabric efficiency and carbon dioxide emissions, all new dwellings will need to comply with primary energy demand metrics taking into account affordability and actual use at the property.

The role of heat pumps

One of the most prominent players in the no-gas future is likely to be the heat pump. Direct electric heating can work in some instances, but only for smaller, high-performing properties if occupants are to avoid excessive fuel costs.

A heat pump is an electrical device that extracts heat from one place and transfers it to another – rather like a fridge, although the aim is to keep that space warm rather than cool. Air-source heat pumps absorb heat from the outdoor air, while ground-source heat pumps draw heat from the earth or ground water.

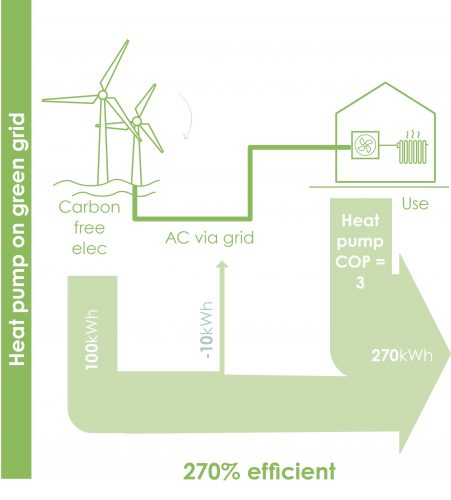

Both transfer the heat they draw to a heating or hot water system inside a dwelling through an exchanger. Unlike gas boilers, which have an efficiency of around 90%, heat pumps can be up to 270% efficient by using input energy to collect heat from the air, ground or water, as shown in Figure 1.

One of the most critical issues for pumps is that the heat is provided at lower temperatures than it is sourced, because they operate most efficiently at around 55C in supplying radiators or underfloor heating.

A highly insulated, airtight building envelope is therefore required to achieve efficiencies of 270% and avoid oversizing pumps or running them incorrectly. This entails careful design in new builds, and can be fraught with difficulties in existing homes where thermal performance issues and dampness are prevalent.

The Future Homes Standard consultation identified an uplift in the cost of a new no-gas home of around £5,000. A Carbon Trust report published last August identifies the average cost of heat pump installation along with new higher-output radiators in existing homes as around £12,200, compared to a boiler replacement cost of around £2,500.

However, according to the Carbon Trust’s Heat pump retrofit in London report –which was published in August 2020 – it costs around £48,000 on average for a deep retrofit; that is, a full upgrade of the thermal envelope to make it airtight and install new building services such as heating, hot water and ventilation systems to minimise energy use and fuel bills and ensure high levels of occupant comfort. The average baseline is for an average of property types 01 to 11 when modelled.

Given this cost, financial support is clearly needed. However, the government’s domestic Renewable Heat Incentive has only funded around 9,900 installations per annum in the UK since 2014. There is a clear gap in finance, and current policy is unlikely to fill it.

The Green Homes Grant was intended to provide some support to private owners. Although there was high take-up, supply chain capacity was lacking, and the scheme was poorly managed, the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee found. Consequently, the scheme is being scaled back.

The supply chain is a key issue. The UK’s independent Committee on Climate Change estimates that 19m heat pumps will be required by 2050, which roughly matches the prime minister’s ten-point plan commitment to 688,000 installations per year by 2028. While this may sound like a lot, some 1.67m gas boilers were fitted in 2019, according to the Heating and Hotwater Industry Council. The issue is that there is a skills gap for installing new technology, and a failure to transfer market capacity from gas to heat pumps.

Hydrogen potential

In addition to setting higher standards through the Building Regulations and prohibiting the use of gas boilers in new builds, the government is also pursuing a hydrogen strategy.

Hydrogen may be considered a zero-carbon fuel because when it is burned to produce heat the output is water. In theory, we can introduce more hydrogen into the gas network to reduce its carbon intensity.

So-called green hydrogen is created through electrolysis using carbon-free renewable power, whereas the gas supply industry is advocating blue hydrogen produced using natural gas reformation and unproven carbon capture technology.

This is a complex chemical process using natural gas, high pressure steam and catalyst to produce hydrogen, carbon monoxide and a little carbon dioxide. The carbon monoxide and a catalyst are processed again to produce carbon dioxide and more hydrogen.

There appear to be problems ahead with both green and blue approaches, however. A full switchover to green hydrogen will require 50% additional renewables capacity nationally, as the process is only around 46% efficient, compared to around 270% for heat pumps; blue hydrogen is slightly more efficient at 58%. But both options are fraught with difficulties, such as the replacement of pipework in buildings and determining who will pay for the upkeep of the external gas networks as users dwindle.

It is tempting to think that hydrogen may provide the proverbial silver bullet for historic and existing buildings that are difficult to retrofit, and which are currently heated by gas. But the likelihood is that hydrogen will be used in industry, on new local networks, and as a form of renewable energy storage.

Retrofit strategy

The UK has the oldest housing stock in Europe, with 85% of existing homes reliant on natural gas and 25% of carbon dioxide emissions arising from residential gas networks. To achieve net zero by 2050, we’re likely to have to undertake 27m deep retrofits, or incremental alternatives where the upgrade is carried out stage by stage due to constraints with finances or the owner’s asset strategy.

Our homes are our biggest national infrastructure asset, but we have a complex, multifaceted market and that asset is not treated strategically. There is no big plan, but there have been quite a few shorter-term interventions and historically confusing signals.

In December, the Construction Leadership Council launched a consultation on establishing a national retrofit strategy, which identified a four-phase plan between now and 2040. It estimates that 500,000 new professionals and tradespeople will be required.

But the council also believes that energy savings, employment, and a reduction in the number of excess deaths from poor health caused by underheated or overheated homes will mean there is an overall £2 return on every £1 invested. The consultation, which closed on 1 March, considered multiple proposals, including creating demand from private owners through stamp duty rebates, reduced VAT, direct grants, low-interest loans and green mortgages.

Strategic active asset management

But what can stock-holding organisations do to prepare for a future without gas? The simple answer is data, data, data; or, strategic active asset management.

The end of gas can’t be considered in isolation. There are a few property archetypes where electric-for-gas replacement will make sense, in terms of both capital and running costs; but organisations need to collect all their data on hard-to-heat homes, airtightness, ventilation and the existing condition of components in order to get a full picture.

In other words, a 29-year-long stock-based strategy is required to get to net zero, and it won’t include much natural gas. Such a strategy needs to be modular so that it can identify packages of work or components that can benefit from available funding such as the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund Demonstrator.

This is likely to recommend incremental and whole-house retrofits as well as demolition and rebuilding of some stock – and will also involve support for training to address supply chain and skills issues.

Setting a standard for retrofit

But how do we avoid problems such as low quality, the performance gap and increased bills – not to mention residents’ bad experience of some past retrofits, where following the money often resulted in some poor and perverse outcomes?

Anything more than a simple gas-to-electric heat-source swap that involves improving the thermal envelope and ventilation should be carried out as outlined in PAS 2035 Retrofitting dwellings for improved energy efficiency. Specification and guidance. Sponsored by the government’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, this is a key document in a framework of standards for retrofitting existing buildings for energy efficiency effectively.

As a quality control process, PAS 2035 advises the appointment of specific roles, such as retrofit coordinators, and involves risk assessment as well as the production of medium-term improvement plans for each property.

When it comes to retrofitting heat pumps, one of the key issues is that they are more effective at lower temperature flows and returns. They therefore depend on an efficient thermal envelope, effective airtightness and ventilation strategies, and longer, more consistent levels of demand, with less expectation that the heating can simply be switched on or off to quickly heat up or cool homes.

Funding support

Support in the form of funding will be necessary to cover the capital cost of heat pump installations and the building envelope performance upgrades necessary to achieve the net-zero target.

One such source of finance is the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund Demonstrator, which is aiming to scale up retrofits in social housing and start to encourage the development of a supply chain. At Baily Garner, we are currently working with one of our clients on a project funded by the demonstrator that improves the thermal envelope and airtightness of 180 homes, and on many other properties we will be introducing an 8.5kW air-source heat pump.

The Greater London Authority has also recently launched a partnership to implement Energiesprong retrofits at scale. Uptake by householders is encouraged by a performance guarantee, with the refurbishment funded by the difference between the utility bills before and after the retrofit.

Energiesprong is a whole-house retrofit approach with the aim of limiting space heating demand to 30 kilowatt–hours per square metre per annum. This is very challenging, and will often include an air-source heat pump and an all-electric approach.

The approach is not prescribed, but is likely not to involve gas due to the legally binding obligation to achieve net-zero carbon. We at Baily Garner are currently working with a local authority client on a pilot scheme of eight properties. As a small, stand-alone project this faces prohibitive costs, but it is hoped that scale will improve viability.

From a new-build perspective, the 2025 no-gas deadline is looming, so the industry needs to rely on tried and tested measures – hence the significant uptake of heat pumps. Consideration of such technology along with early engagement of building services and sustainability experts in conjunction with ensuring higher-performing fabric is essential.

When it comes to retrofitting existing housing stock, it’s clear that funding and training will play a key part in whether we can meet the net-zero targets by 2050. But if we can strategically consider the stock as a whole, there are options to make meaningful improvements and significantly reduce the use of gas.